1. To sign up, fill out the form below

2. Receive the collection kit

3. Start your collections!

Published: Jul 11, 2020

Evolution in your backyard

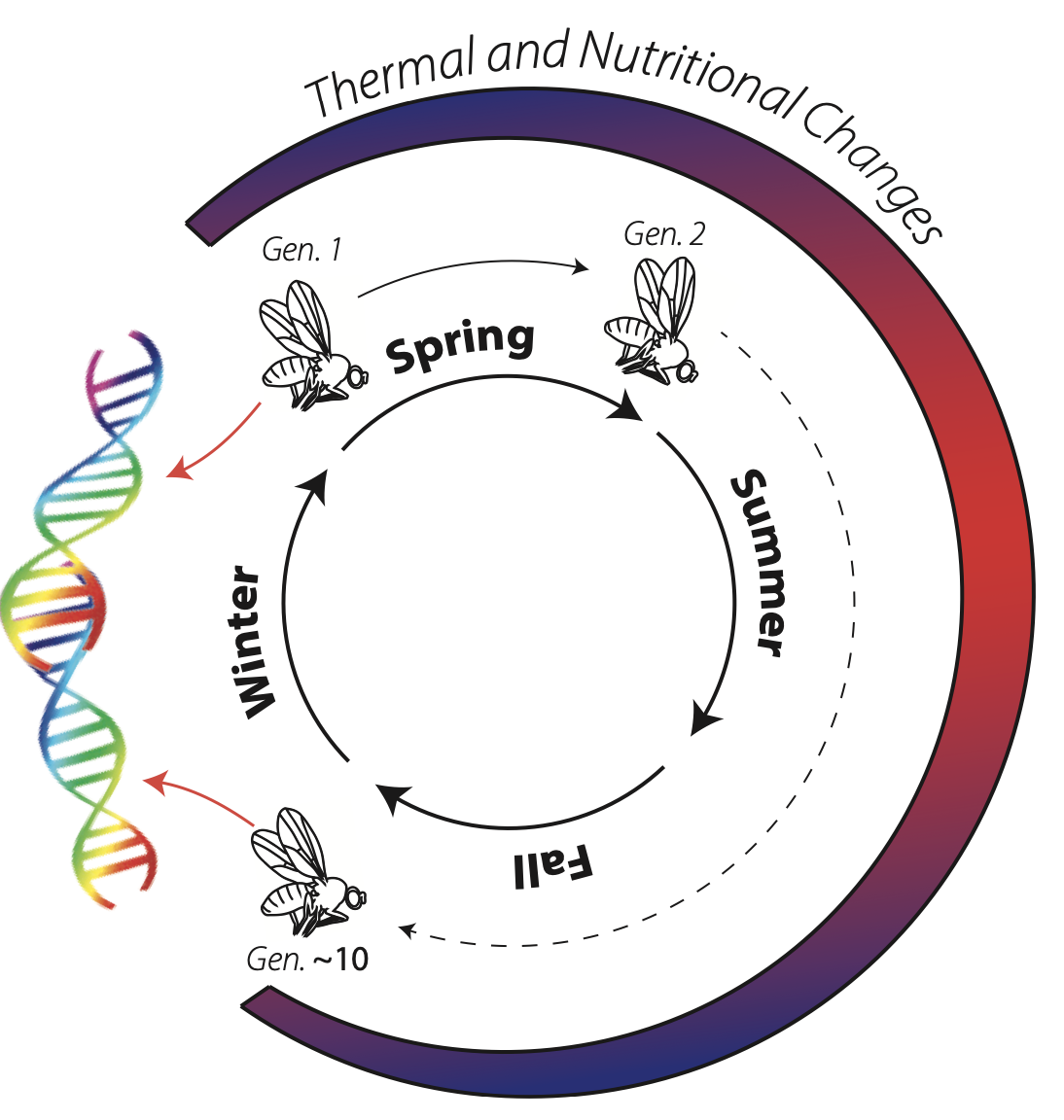

For many plants, animals, and fungi, we think of the seasons as a cycle of growth and dormancy. What is growth? For an individual, growth is the transition from one stage of life to another; the accumulation of resources. However, for a population, growth is the increase in population size across time. Many of the organisms in your backyard - for instance small invertebrates and weedy plants - have rapid development time, and are able to undergo multiple generations between spring to fall. The environment changes during the course of the growing season, imposing variable natural selection through time. As these populations grow, and eventually decline, they evolve in response to these changing environments.

DNA as a historical record

We can observe evolutionary change in populations through the analysis of DNA. Because most individuals in a population have slightly different genomes, we can infer the evolutionary history of the population and species. In some cases, such patterns reveal the more distant past, for instance large scale migration events. In other cases, we identify regions of the genome that have recently undergone adaptive evolution. Patterns of variation not only tell the story of the past, but also the present. We can track evolutionary dynamics in real-time. And, we can do it from your backyard.

Fruit flies and compost piles

Your compost pile is teaming with life, and fruit flies are an important part of that ecosystem. Fruit flies typically eat bacteria and fungi that decompose your scraps, and are therefore part of the decomposition cycles that make the world go around. Over the course of the summer, your pile will likely be inhabited by about a dozen species of fruit flies, in addition to many other flying, walking, and crawling invertebrates. For some species of fruit flies, 10-15 generations can pass between the spring and fall. Populations of fruit flies evolve over the course of the growing season as aspects of the nutritional and thermal environment change. By sampling fruit flies from your compost pile over the growing season, we can track the evolutionary dynamics of fruit flies in real-time.

Will you commit to sampling and preserving small flying insects from your compost piles 2x per month July - December?

*If you miss a week or two, that’s okay!

Participate in a world-wide effort

Your participation in this project will contribute to an ongoing, international collaboration of fruit fly biologists to study the genomes of flies sampled throughout the world. Your samples will represent a unique contribution from Virginia. Read more about this effort at https://www.droseu.net

To sign up, click here

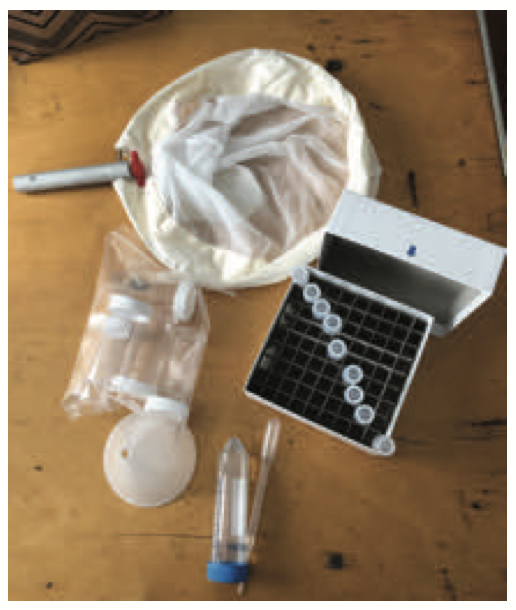

We supply everything you need to participate!

The Kit

- Drosophila net

- Collection vials

- Preservation tubes

- 75% Ethanol

- Eye dropper

- Specimen labels

- A funnel

- Collection Log

- Collection Manual

Here is an example of a filled collection vial. Flies were collected by gently kicking a compost pile. There are ~50 flies in there, so multiple vials might be necessary to get the requested ~200 flies.

Learn how to collect flies with this video:

Here’s what you’ll be doing 2x a month:

Goal: We want you to sample ~100-200 fruit-flies every several weeks over the growing season and into early winter.

Fruit flies are most active in the early morning (6:00AM-9:00AM) or evening (6:00PM-9:00PM), and will be easier to collect then. They may be hiding in the heat of the day.

To sample, first hold a large collection vial in your non-dominant hand; keep the lid nearby. Then, with your other hand, sweep your net back and forth in a gentle motion and kick or tap your compost pile with your foot.

Many small flying things will emerge. Capture as many as you can in your net. Keep sweeping the net back and forth to keep the flies in the tip of your net. Then, in a swift motion, place your collection vial in the net tip and tap the flies into the vial. Using a tapping motion, tap the flies to the bottom of the vial and cover the vial with two or three fingers, tapping the flies down on your knee. Then, take the lid and screw it onto the vial. It might take a couple of tries. If the flies escape, give them a minute to settle down on the pile and then try again.

Your sample likely contains anywhere from 10-100 flies and multiple species. Take a look at your vial. How many unique species do you think there are? Write down your estimate on your sample label.

To preserve your flies for genetic analysis, you will be storing them in 75% ethanol. First, take a preservation tube and fill it ~1/3 full with 75% ethanol using your plastic eye-dropper. Place your funnel in the opening to the preservation tube and seat both upright, using your specimen box. Using a tapping motion, tap your vial down to knock the flies to the bottom of the collection tube. Unscrew the vial and place two or three fingers over the top. In a swift motion, invert the collection vial into the funnel and tap* the flies down, into the ethanol.

Ideally, you will fill the preservation tube more than half way full with flies. You might need to take multiple samples from your pile on a collection day to get that many. If, after two or three nettings, you cannot get the vial half full, then stop. Once your collection is complete, firmly press the cap down (it’ll snap closed) and place vial upright in the freezer. This ensures that DNA will be preserved in a high quality state.

Record your sample by filling in the date and time of collection on your specimen label and apply to the vial. Please use a pencil or ball-point pen, as Sharpies tend to bleed when exposed to ethanol. Your labels will contain a unique collector ID (that’s you!) and a sample number. For safety, record the sample number, time, and

date on your collection log.

We will pick-up your samples at the end of the year (December 1-15 2020, or earlier upon request).

We will remind you to collect every two weeks via text message or email (your choice).

*Cold shock your flies. If you are having a difficult time transferring your flies from the collection vial to the preservation tube, place the collection vial in the freezer for ~1-2 minutes. This will slow the flies down.

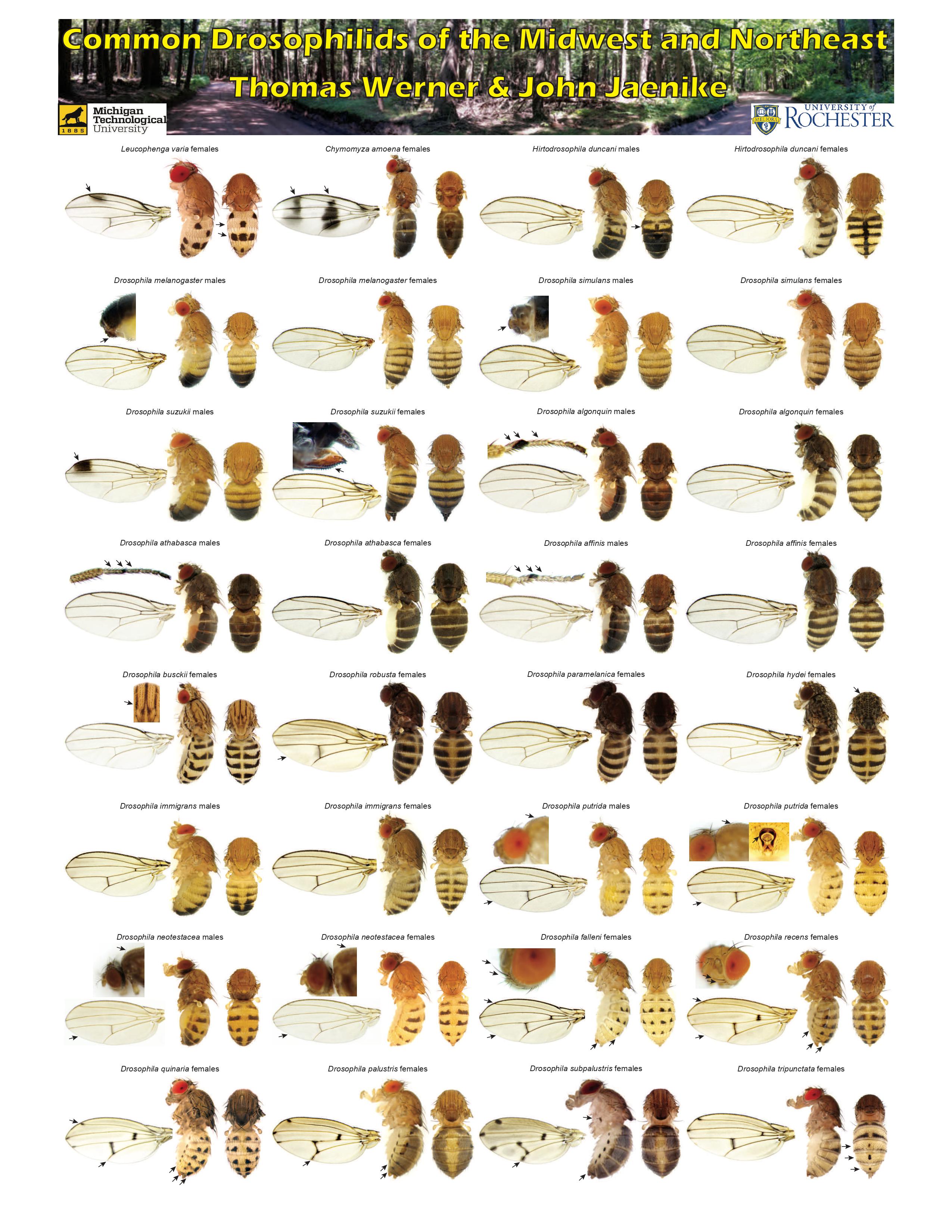

What species of fruit flies can you expect to find? In Central Virginia, we typically find about 10 species of flies. Some of these species are endemic to Virginia and North America. One group of endemic species that you can easily spot are species in the affinis group. They tend to be quite dark and males have bright red testicles that are visible on the bottom of their abdomen. Other species you find are invasive, and have established in North America over the last several hundred

years. One of these species is the genetic model species, Drosophila melanogaster. Even though this species is not native, it is capable of overwintering and populations in your backyard might be permanent. Most of the species you collect are not economically important pests. One exception is Drosophila suzukii, the spotted wing Drosophila. This species has colonized the world in the last decade and is a major pest on soft-skinned fruits. An excellent resource for species identification

and natural history of many of the species in our area can be found in Drosophilids of the Midwest and Northeast (2018) by Werner, Steenwinkel, and Jaenike

https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/oabooks/1/ (the 2nd version includes bedtime stories for kids!)

What are we going to do with the flies you collect? Samples that you collect during this first year will be sorted by students at UVA. We will then sequence the genomes of one species you collect, D. melanogaster, using a technique called Illumina sequencing. This approach will allow us

to track the frequency of every genetic variant in the genome through the growing season. This is the basic approach that we use to study the evolutionary process. The remaining samples of species will be retained for future work.

The 2020 Backyard Evolution collection effort is a pilot project that will augment ongoing research in the Bergland lab. We aim to include ~35 participants this year, and will be pursuing National Science Foundation funding to expand the program to include more of the state for 2021-2026. We look forward to working with you to incorporate your ideas to improve this project and to increase outreach and education efforts.

Statement on the evolution of diversity. In many species, populations differ from each other and these different varieties are sometimes locally adapted to the environment where they are found. It is easy to relate this ubiquitous biological phenomenon to racial categories. We cannot confuse ancestry and evolutionary history with race. Racial labels reflect the imposition of power of one group over another and arbitrary distinctions of who is superior and inferior. There is no biological justification for oppression. There is no better and worse, just different.

COVID-19 safety

Collection kits will be dropped off at your house with no personal contact.

Privacy statement

We will only use your contact information to remind you to collect. For research purposes, we will use latitude and longitude associated with your house along with the answers to your survey questions. Your name will not be linked to your address for any publication and your house location will be only presented as latitude and longitude (within ~1/2 mile of actual address).

ANY QUESTIONS?

Email virginia.backyard.flies@gmail.com

TO SIGN UP, VISIT THIS LINK

Drosopholids of the Midwest and Northeast

Check out this excellent guide to drosophilid flies by Thomas Werner, Tessa Steenwinkel, and John Jaenike

here .